Янв 31

Dance, battle and ritual

The phenomenon of Indian military practices cannot be understood and explained in the context of modern views on Oriental martial art or self-defense in general.

In addition to the value of the practical and applied aspects of these practices, which is not entirely clear from this point of view, their internal content, «source code» or fundamental content, remains terra incognita.

They have no training imperative of «warrior spirit» or call to follow either path. In addition to the above, it should be noted, that they have strong demonstrative component, sometimes disparagingly called «dancing» by followers of modern martial arts. A small historical and cultural journey clarifies the previously undescribed points and give an insight into the fact that there is much more historicity, heroism and authenticity in the «dancing» of Indian military practices than in the more brutal in the modern sense of martial arts. Strange as it may appear, the polestar in this journey is bells…

Bells

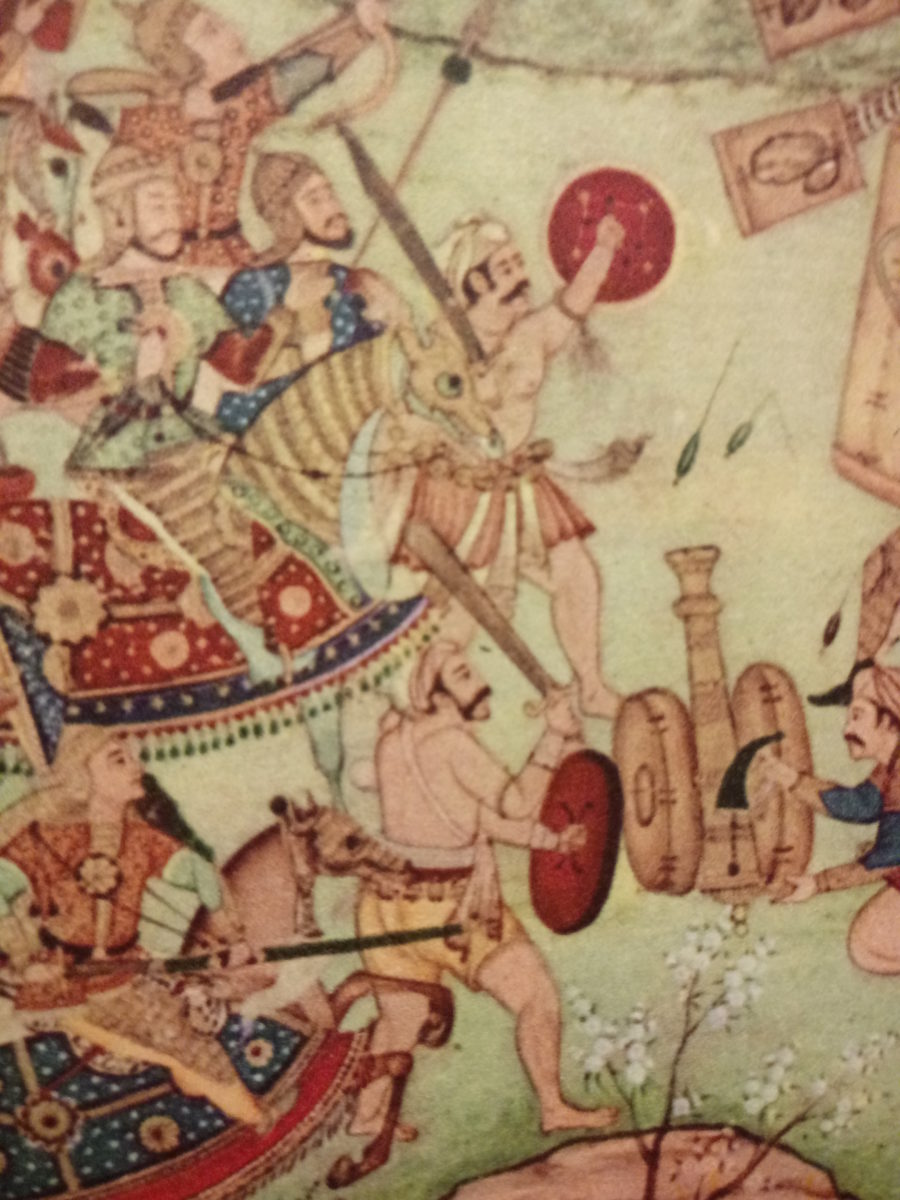

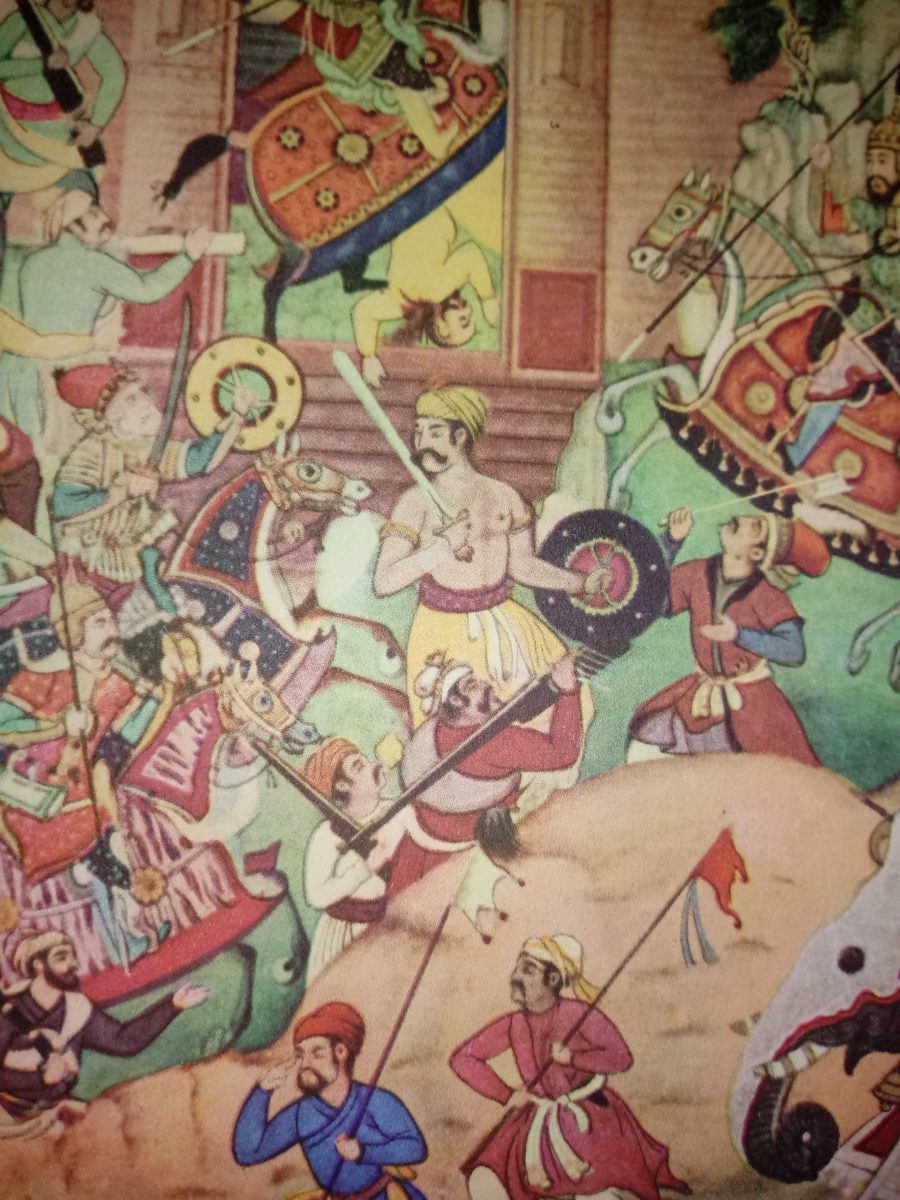

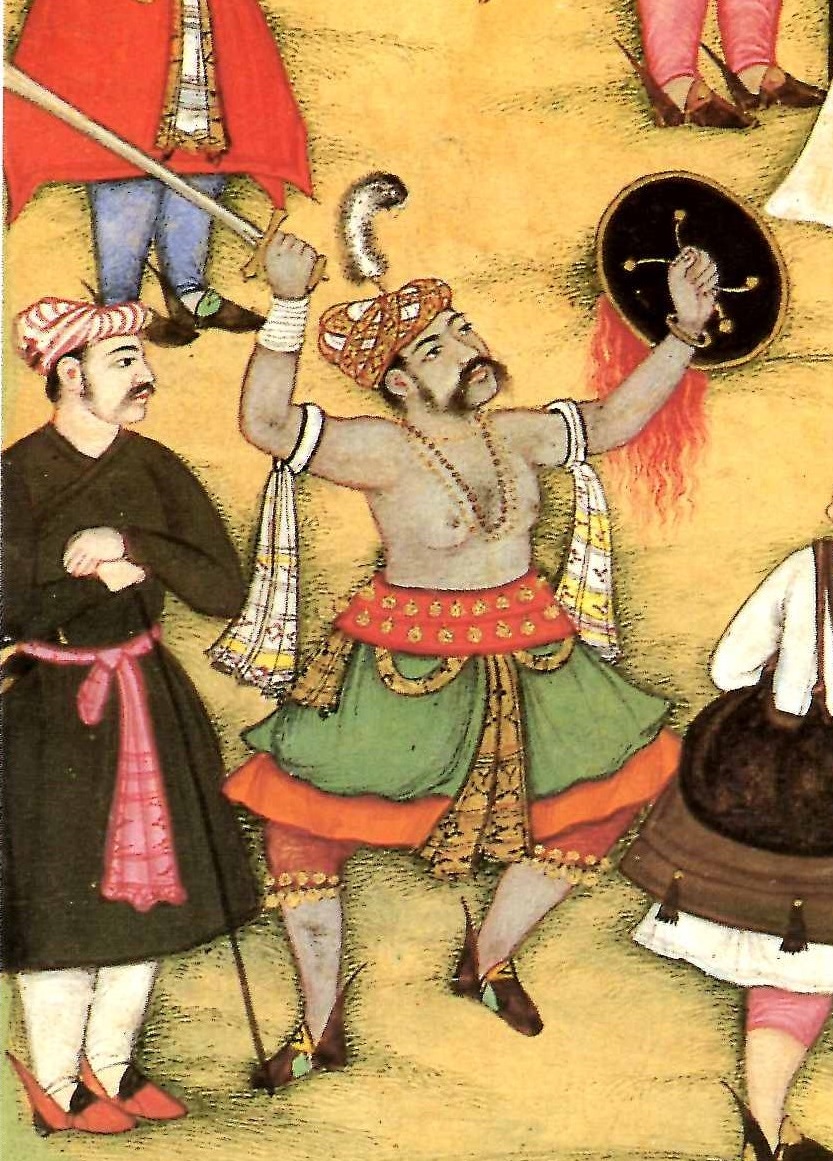

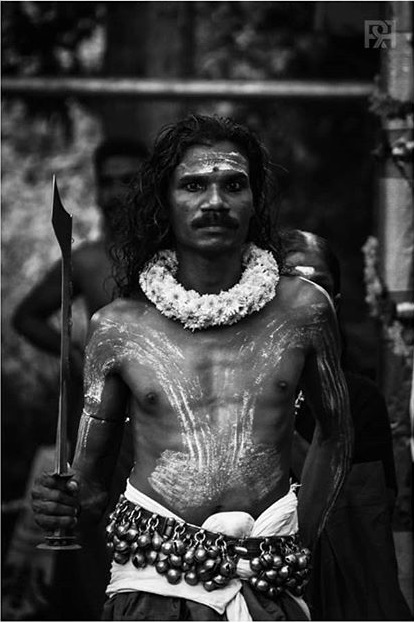

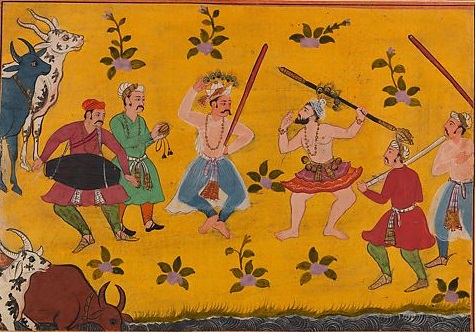

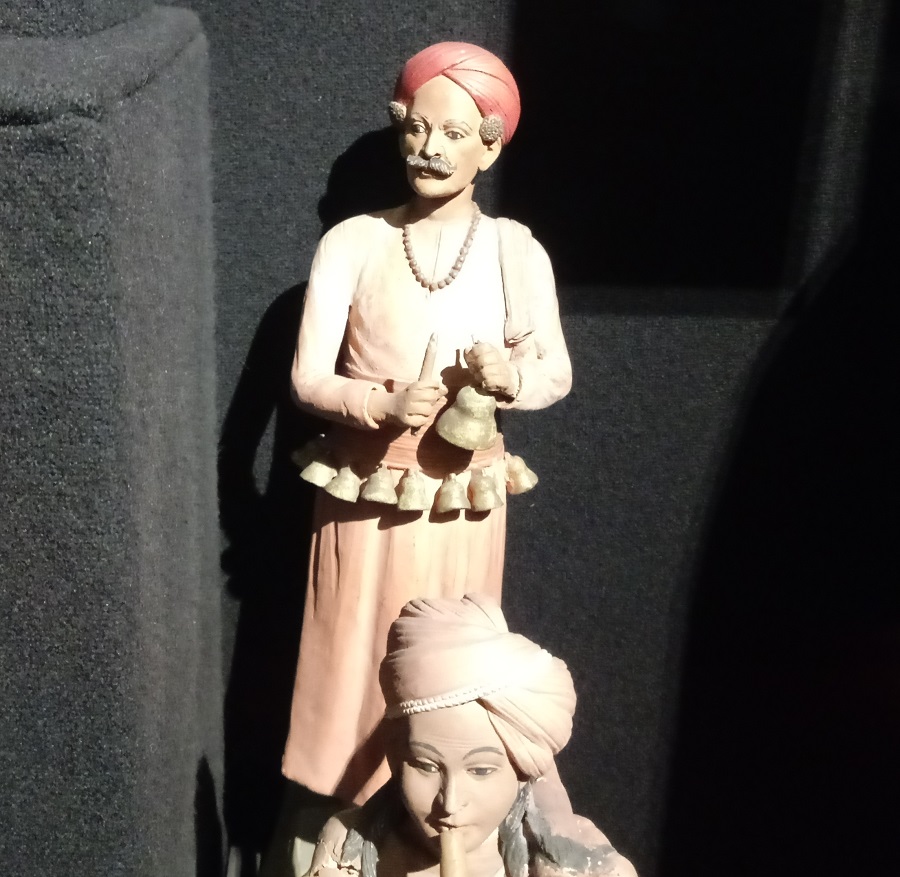

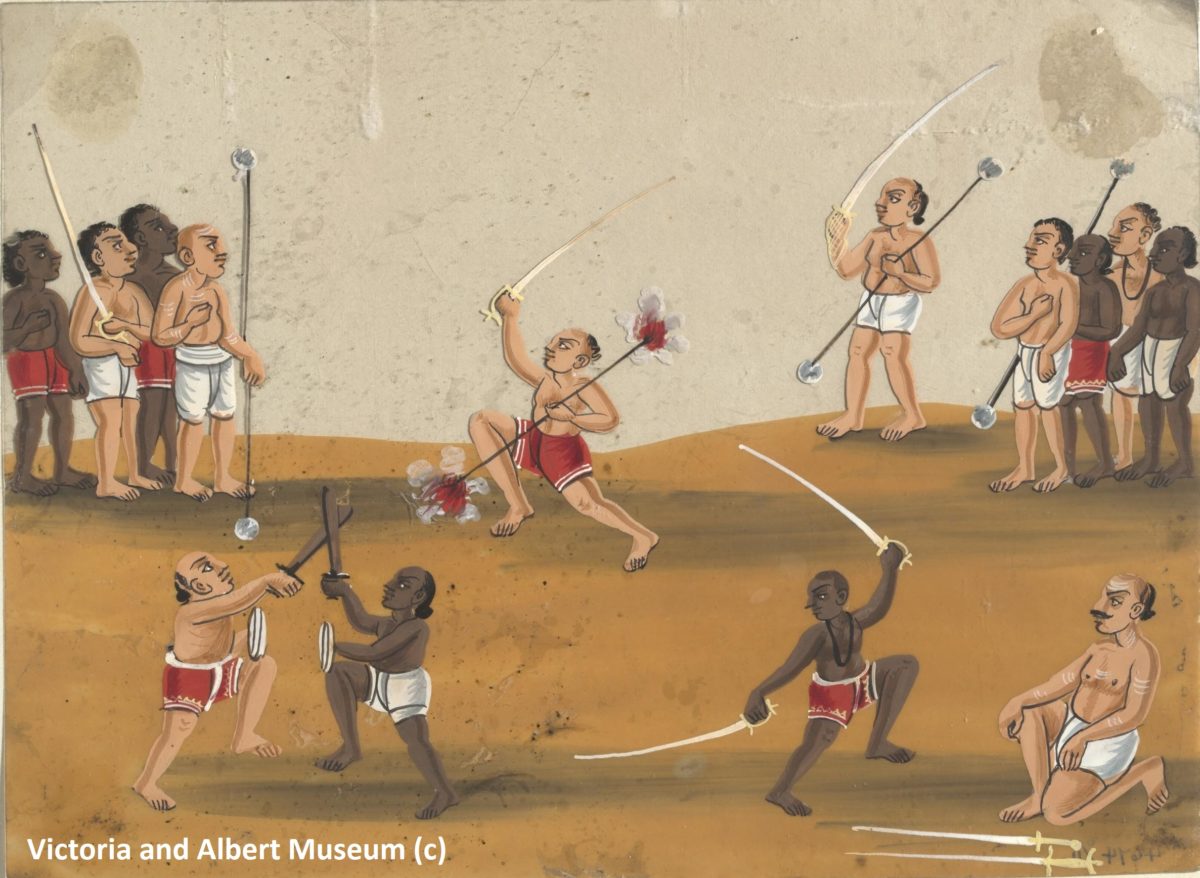

In Mughal court painting of the late XVI – early XVII century, known for its realistic approach to images (unless, it is about illustrating fairy-tale or mythical themes), in battle scenes there were often unusual characters. They were dressed and equipped in the Indian manner, and stand out of the Mughal army, while occupying the central places in the composition and fighting heroically in the front ranks. The distinctive features of those warriors were the absence of armor, often the upper part of clothing, armlets (sometimes with brushes) or bracelets on the forearms, anklets (bracelets on the legs), but their main distinguishing feature was belts with bells.

Equipage with bells is mentioned in written sources. In the poem «Prithviraj Raso» Rajputs are described as ascetics and have all the attributes of ascetics; it emphasizes the importance and sacredness of the battle. Warriors-the Rajputs have the plumages of peacock feathers, they sound the shell and they wear bracelets with bells. James Tod in the early XIX century described the bhils, an indigenous people of India, supposed to date back to the Dravidians. They were culturally close to the Rajputs and were considered as their blood brothers and brothers in arms. James Tod wrote that their leaders and the main warriors in the battlefield wore belt with bells as a distinctive mark.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (c)

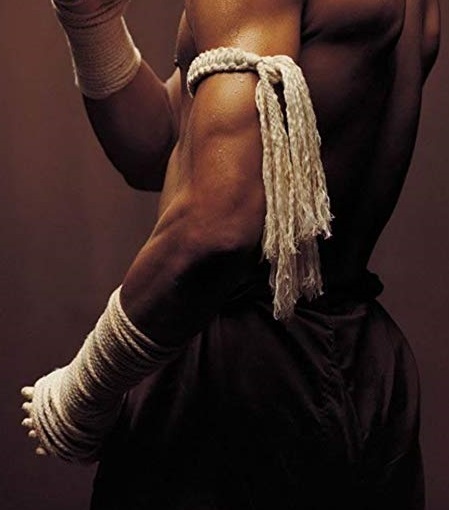

These numerous evidences make it impossible to write everything off for artistic imagination of authors of the miniatures and conventionality or not historicity of the represented scenes. The attributes used by those soldiers still remained in the world of martial arts in some martial arts of South East Asia, having the original Indian origin, such as a bandage on the shoulder «pra jiad» («pratyat») and protection of the wrist and forearm by tightly wound cord, and, in fact, the performance of ritual dance before the fight.

But let us follow the bells further…

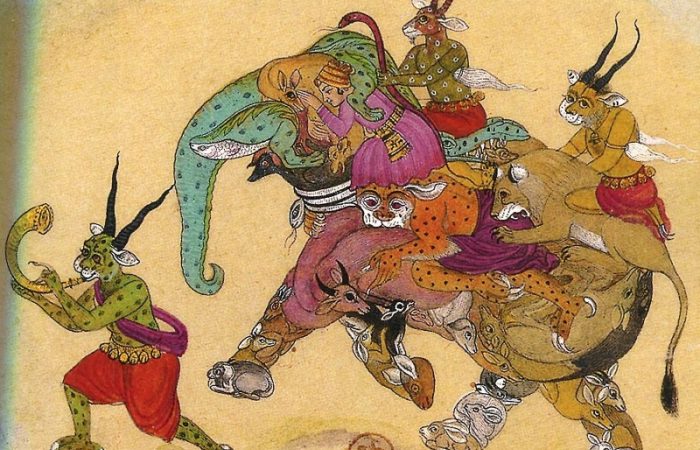

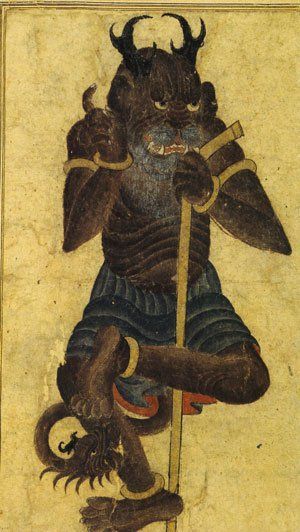

Demons

When looking for the possible analogies to the specified characters, in Mughal painting of the same period, there are images of the demons dressed in the same manner, as the Indian wrestlers and swordsmen but in illustration of fantastic or mythical plots. There is a certain dissonance: in many cultures, bells are designed to scare away evil spirits and should hardly be their direct attribute.

-

The Walters Art Museum -

The Walters Art Museum -

The Walters Art Museum

The first image of similar demons is found in Iranian painting of the XIV-XV century. If trace the origin of this very stable image, such creatures with bells were mentioned only in Turkic folklore.

-

-

-

https://clevelandart.org/art/1982.63

There are known description of a demon Jangolos, hung with bells. The name of this demon may ascend to the Turkic expression «jangil-jungool», «with noise». Also «Jangolos» is also a bell of the sheep.

Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography

Those demons were dressed in a manner unusual for Iran or Central Asia. But such a manner is usual enough for more southern regions, which individual representatives looked highly intimidating in the eyes of «enlightened» representatives of Central Asia and Middle East and could serve as a prototype of «demons», either due to color of the skin, or incomprehensible dances and clearly «demonic» rituals…

Shamans

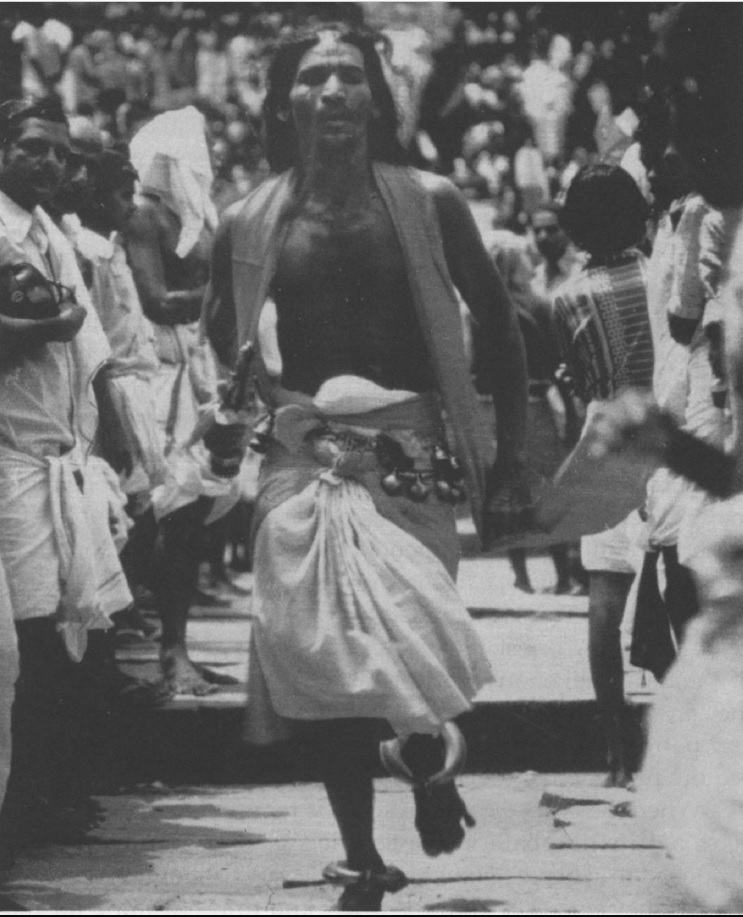

These are priests or shamans of various especially South Indian religious faiths, who did not become the characters of the Mughal miniature in themselves, but whose cults date back to the pre-vedic tradition.

The image of the ministers of these cults could influence the imagination of representatives of the Turkic or Arab-Muslim world: in addition to the unpleasant and intimidating appearance of shamans, there was a fact that in the view of the observer devoid of knowledge (and prejudices) of modern pragmatic-technically thinking man, the spirit that possessed the shaman, was inevitably identified with the visual image and appearance of the shaman.

The object of worship in those cults were and are the militant aspects of the mother goddess Durga or Shiva. An integral part of the ritual is colorful performances, dances with weapons.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NRngepRn6dY

The priests of Durga in the Northern regions differed from their South Indian counterparts only in the amount of clothing, which was due, rather, to climatic conditions. Nepalese shamans, in addition to a belt with bells, also wear a peacock feather on their head.

In the specialized literature, there is a variety of opinions about the purpose of the bells on the priests and shamans which can be reduced to one somewhat controversial formula: bells scared off «evil spirits» and attracted «good ones». The way it is possible will become clear further, now it is better to focus on another opinion, according to which a series of attributes used in dances and sacrifices of Indian shamans directly dates back to military traditions or closely related with them. For example, in the brahmanas, weapons terminology is used to refer to the tools used during sacrifice, and the use of anklets in ritual dances is considered to be a direct representation of military anklets.

In one of the oldest surviving works of Tamil culture (which eventually became part of the General Indian culture), in the treatise Tolkāppiyam, you can find similarities and even a mixture of ritual and military dances, containing a demonstration of weapons skill.

Kalanilaikkuttu is a dance in honor of young warriors, who fought in first ranks, keeping the enemy at bay and ensuring, thus, safe retreat of other troops. In case of victorious return of those soldiers alive, they were awarded with anklets, and dances were arranged in their honor.

Kalal or virakalal (vira is heroic) is a military anklet. It was not only an ornament, but a symbol of bravery and military force. The fact that anklets were mentioned along with a bow, sword and shield as attributes of a warrior, shows its importance. These anklets were awarded for fits. Fixed term: «anklet warriors.» It was often sounding bracelets, not just jewelry: «The hero’s anklets jingle loudly!» (Tamil poem of the VI century A.D.).

Even in the Rigveda, Maruts were compared to kings as warriors with bracelets on their shoulders and ankles.

It is known that the tradition of wearing military bracelets existed in the XIV century A.D. in Hoysala, the South Indian Empire, where bracelets on ankles were used as a distinguishing feature and were made of gold.

Another dance was arranged in case of the death of the king, leader of the army in the battlefield. In this case, all other kings-leaders, regardless of which side they fought, surrounded the fallen and performed a dance, including a demonstration of weapon possession.

The treatise Tolkappiyam also gives information about the relationship between ritual dances and certain prayer states, dating back to an era much older than that quite ancient treatise. This connection can be traced in the cults of Murugan, the South Indian God of war, and his mythological mother-goddess Kottravey, later identified with Durga. In those rituals, the priest danced with the spear (vel). One of Murugan’s names is Spearman (Velan).

As we can see, there is an obvious, but still inexplicable link between warriors wearing belt with bells dancing with weapons, when not in battles, and priests-shamans of militant cults equipped in a similar manner and dancing with weapons as well.

What is common between warriors and shamans who dance similar dances and use the same attributes?

Place

Indian military practices with weapons were closely related to traditional wrestling, and before modern times training in wrestling and weapon skills occurred simultaneously. Even nowadays one may trace direct analogies between the arrangement (external and internal) of wrestling and, not that many nowadays, weapon akharas.

The term «akhara«, as known, has the main meaning of «school» (meaning «gymnasium») in the sense of an offshoot of the teaching of a certain spiritual orientation or school, where there is training in any athletic or related physical and sports skills arts, or «site», as a plot of land where such training takes place. It could also mean a meeting place. Akhara could be identified with the battlefield. Thus, in the mentioned poem «Prithviraj Raso», the Rajput troops are described as follows: «in the battlefield they are like wrestlers in the arena, and their «troops rush across the battlefield as through akhara.»

Similarly, in the cult of Murugan, the South Indian God of war, later identified with Skanda, or the goddess of war Kottravey merged with Durga in Hinduism, the place for rituals where priests danced with swords in their hands, belts with bells and anklets, was called «kalam». «Kalam» is also a place for meetings, a field for sowing and harvesting, a place of sacrifice and a battlefield. Durga Kottravey is a goddess, the giver of victory in battle, but she is also a goddess of dance.

Moreover, South Indian cults used to identify God and his place of worship, which became the location of God. God became the place, and the place became God.

In akhara there is a temple built, as a rule, over the burial of a famous ascetic. Ordinary people come here after a working day to recover strength, or visit this place in their spare time to get a affect, as they believe, to their health. Even water in akhara, flowing from exactly the same well or water pipe as in the neighborhood, is considered to be cleaner or healing.

Definitely, kalam or akhara are not natural «places of power» or not only such places. They owe their status not least to the actions that took place there, and cannot exist apart from those actions. So what was going on or what was there?

Energy

It should be about «energy», but, unfortunately, it just so happened, that the arbitrary use of this term in relation not only to martial arts, but also to other various kinds of practices, created much more difficulties than brought clarity. Therefore, it is better to use traditional concepts, born not «from the mind», and it should be about two very similar ancient Indian phenomena, designated in the Vedic tradition as «tapas«, and as «anangu» in the Dravidian.

Anangu is of a fiery nature, it is «heat». This is that very heat, which in ancient Tamil concepts was contained in phenomena, quite not coincidentally in many cultures described with appropriate adjectives, such, for example, as «ardent love», «ardent hate» or so. Anangu, created from root «an» («an» means «lie within»), was also in such places and things, as hearth, weapons, musical instruments, in dangerous animals, such as lion, tiger or a snake, in some trees, in robust hands and legs of warriors, in feminine breast and in young women as a whole, in everything that somehow has power and, therefore, is dangerous or, contrary, provides potential opportunity. Thus, anagu could be both useful and creative, dangerous and destructive. Anangu, for example, was also found in dead bodies and in burials. Blood contains anangu, and that is why it is offered to Durga during the rites of dissecting the chest or forehead with a sword. It is still practiced all over India, although it is now more common to incise the tongue as a more gentle or, conversely, more frightening procedure. Anangu is where blood is shed: in the place of sacrifice or the battlefield.

In akhara, in the battlefield, in the site in front of the temple and in place where the God is and sacrifices are committed, anangu was present. In Akhara, the warriors learned to control the anangu contained in the weapon, so that they could then use it to control the anangu in the battle, and in the place in front of the temple, the priest controlled the anangu contained in the victim, in its «hot» blood, and doing so he established a connection, «controlled» the gods.

Uncontrolled energy and uncontrolled heat are dangerous. They shall be localized and «tamed» to become a source of power that can be used safely. The most uncomplicated and straightforward way to control the heat, or rather, just to make it safe, is to cool it. The most accessible methods of cooling were garlands of cool flowers, wreaths of leaves, rubbing the body with saffron, turmeric or sandalwood paste, decoration with peacock feathers, or, for example, putting a «cold» stone over the grave or in certain places.

In what other ways could anangu be controlled, especially considering complex forms it could take, in what diverse phenomena it could be contained, and how it could appear in different ways?

Action and performer

Human culture at the early stages of its existence was not only and not so much a way of describing the external world and its phenomena, but first of all it was about filling them with meanings for further understanding and interaction with them. Filling phenomena with meanings, giving them meaning, or, in other words, sacralizing life, these are the ways of establishing mutual understanding with external and internal powers, control over them.

There is a very simple analogy, which will immediately clarify what is all about. A quite clear mechanism of procreation in all cultures of mankind was endowed with meanings and ritualized in wedding ceremonies in order to establish order and eliminate chaos, and the tradition of wooing is still fully consistent with the principles of «establishing control» over the anangu of a young girl.

Ritual or rite, i.e., essentially magical action, to a degree, was behind any form of art or creative performance. That action could be anything, especially at a time when there was no separation of genres and when even speech was perceived as an action.

But there should be a performer for any action. In traditional cultures, performers appeared where there was a need to interact with meanings, where mediators were needed. Even the court performance act, entertainment performances for the ruler in the palace were originally a serious ritual, which had the purpose of controlling the «sacred energy» of the king and the country as a whole, maintaining it normally, ensuring the welfare and prosperity of the population.

In other words, the performer acted as a mediator, as a priest. Only if the priest in the conventional view established a connection with the gods through sacrifice, the performer sacrificed action, just as the Vedic priest could sacrifice speech, hymn. A dance was one way of sacrificing action, a way of controlling the space or place where God dwell, and therefore a way of interacting with him.

What is the control and interaction with the power? It’s connecting with it. If a dance or a performance on stage can establish a connection between the performer and the audience and convey a corresponding appeal to the feelings, emotions and consciousness of the latter, why can not the same be done in relation to the gods and powers? If the artist receives the emotional support and gratitude of the audience, why should the powers and gods be less grateful or responsive?

Obviously, the performer shall be specially prepared and at least not closed on himself: he shall perform his art not for the purpose of self-admiration, self-improvement, search or endless filling of himself, but, on the contrary, giving himself, «putting» himself into the spectator, sacrificing himself.

In other words, the performer placed himself in a ritual (magical) space, in a situation filled with certain meanings, in a ritual situation. The ritual situation is that which is withdrawn from time, that there is one moment despite how long it lasts and has the attributes of the real and the present, has meaning and sense. Thus, through sacrifice (self-sacrifice), the performer was included in the system of cyclic exchange and renewal of vitality, in eternity.

Later, in the Axial Age, this ancient system of values was replaced by the paradigm of transcendent «release» and the change of the vector, previously directed from the individual to the general, to the opposite, directed to the individual, when the performer no longer invested himself in the cyclic system of exchange and eternity, and began to strive to invest this system and eternity into himself.

Battle and dance

So, akhara and kalam are sacred spaces where energy or power works. It is a place of ritual activity aimed at filling with sacred energy. But this activity occurred not only in special ritual places and not only during dance or sacrifice. As was mentioned above, the concepts of akhara and kalam could be associated with the battlefield. And just as dance was a special form of sacrifice, so battle was a special form of ritual activity.

The battle seemed to be a chaos resulting from the disruption of harmony and order that required correction and restoration. During the battlefield, such order restored through the same mechanism interaction with ritual space and establishing control over it.

All Indian culture is characterized by a close association of battle with sacrifice. It is expressed even in a special concept, «sacrifice of battle.» The hero sacrifices his body or his vital breath on the fire of battle («heat» of battle). The opponent is assimilated to a sacrificial animal. Thus, the subject is removed from what is happening, he does not act and is not responsible. He is a victim, priest and recipient of sacrifices, all at once. He is «sacrifice sacrificing itself in sacrifice» like the Creator, Prajapati, who sacrificed himself and became the world. In general, any sacrifice is a symbolic reproduction of this original action, as, in fact, any significant action taking place in the ritual space of sacral life bears the impress of this creative act.

Going back to the basics of this historical and cultural essay, to the images of warriors with bracelets, anklets and belts with bells in the scenes of darbars, court performances and the scenes of battles, it seems reasonable enough that they were wrestlers and swordsmen, champions known for their skill. At the courts, they demonstrated exercises-dances with weapons, participated in demonstration fights, and fought in the first ranks in battles, not separating, as it would seem, such different activities as dancing with weapons, competitive fights and real battles, as Durga did not separate them, remaining at the same time the goddess of war, granting victory, and the goddess of dance.

They did not separate them because those different actions had one fundamental basis, they were ritual acts performed in a ritual space filled with meanings. Even in case of court duels, where swordsmen and wrestlers participated, and where there was a competitive aspect, there was originally a reference to the oldest form of ritual actions, to ritual competitions, realizing the original mythological conflict, when the world balance was restored as a result. Such competitions, not only held in the form of martial arts, it could be a race of chariots or even a game of dice, were an integral part of the «new year» holidays, designed to restore and renew the world, through the ritual reproduction of fundamental myths.

Bells again

By the historical time depicted in Mughal painting, the belt with bells, like armlets or anklets, was rather a reference to archetypal images, irrational and unreal. It is no coincidence that in all the images the warriors who wore those belts were also often armed with old Indian straight swords, as opposed to the surrounding warriors with more modern and comfortable sabres, new weapons, but which did not bear the stamp of antiquity and, accordingly, did not possess the essential authenticity.

Bells are a sign of otherness, a sign of possession of mysterious powers, as in case of a shaman, or just physical strength, as in case of wrestlers. The sign of a madman, irrepressible, a dancer, a shaman, a demon, a deity in his furious aspect. A sign of military fury.

It is the image of Hanuman, the great warrior, who personified both shakti and bhakti, that the cult of physical strength was connected to, which from a certain point took a central place in the Indian martial arts. That cult of force was originally associated with one of Hanuman’s manifestations as shakti: deep forces of nature which are put under control of the subject for achievement of personal, as a rule, physical force and military skill.

But that was not always the case. The fact is that the cult of Hanuman is a relatively late phenomenon. The hero of the epic «Ramayana» appeared in religious texts only in the later Puranic literature between IX and XV century A.D. The religious cult itself was formed fully in the period of the late middle ages. And the first who perceive this cult were the Nath yogis. The following parallels are of considerable interest. The spread of the cult of Hanuman coincides with the invasion of India by the Turko-Afghans and, accordingly, resistance to them. According to the researchers, Hanuman represented «ideal expression of valor, military skills and insight in the representations of medieval South Indian warriors.» In the same period, the impressive armed groups of ascetic warriors opposing the invaders was also noted. The Nath yogis were among the first ascetics who first took up arms.

At that time, the cult of Hanuman was much more complex and had not yet degenerated into a simple worship of physical strength. For the ascetic, the more important attributes of Hanuman were his occult forces, superpowers, physical immortality, connection with herbs and healing, and the celibacy attributed to him.

Possibility of such changes is explained by the fact that Hinduism was not a static religion; throughout its existence, it changed, absorbed popular beliefs and, as a consequence, simplified. Relatively later, on a scale of Hinduism, the worship of Hanuman no longer required elaborate cults, the mediation of priests, or other attributes of temple service. Instead of including oneself in a cyclic system, it was quite enough to «put» Hanuman in oneself: Hanuman’s followers believed that he could inhabit them and transmit his qualities: strength, rage and mastery of weapons. Moreover, for wrestlers and athletes, service of Hanuman was included in their daily practices and trainings.

But the ancient Tamils bells still contained anangu, «ethically neutral force.» That is why they could both attract and repel «evil spirits». As well as weapons can scare or fascinate, take away or protect life. It all depended on how the performer used that power.

Objects contained anangu not because it was physically included in them, but because it was appeared, released through them, as a musical instrument «releases» rhythm and music. It is this appeared and released force that established a connection with the spectator, the space, or the enemy in the battlefield.

The object (a thing, a weapon, a musical instrument) appeared itself through action. The performer appeared himself through the object. That is, the same connection (control) shall at first arise between the performer and the object, and then arise between the object (or rather its manifestation) and the surrounding reality. In other words, the performer shall first learn to control the anangu contained in the object. In this case, the «dance-with-weapon» becomes a «The Dance With the Weapon», an action taking place between the performer and the object, an action filled with anangu. The performer performs a ritual action in relation to the weapon. It is this ritual act where the special treatment of certain objects in traditional societies is rooted. In a world devoid of meaning and fullness, this is called “practice”.

The performer who has ritually established a connection with an object (with his body, with his speech or voice, with a musical instrument, with a weapon) merges with this object, becomes it. Or rather, it is identified with the action of this object: with a hymn, music, dance. And if he is able to «release» this action, to act «without acting», to let it go, then perhaps it will find its purpose and in turn will be able to establish a connection and control with the «auditorium», ritual space or battlefield, and thus be identified with them. And when «Tat Tvam Asi«, then it is not the someone appears in the battlefield, believing, that Hanuman possessed in him, but the goddess of war Kottravey and performs dancing, bestowing victory.